Original Author: Will Awang

Original Source: Web3 Xiaolü

On August 29, 2023, the Southern District of New York court (SDNY) dismissed a class action lawsuit against Uniswap. The plaintiffs accused Uniswap of allowing fraudulent tokens to be issued and traded on the protocol, causing harm to investors and seeking compensation. The judge determined that the current regulatory framework for cryptocurrencies does not provide a basis for the plaintiffs' claims, and Uniswap is not liable for any damages caused by third-party use of the protocol.

Prior to Uniswap's "victory," in the same SDNY court, the U.S. Department of Justice and other regulatory agencies (DOJ) filed criminal charges against Tornado Cash founders Roman Storm and Roman Semenov, alleging that they conspired to launder money, violated sanctions regulations, and operated an unlicensed money transfer business during the operation of Tornado Cash. The two individuals could face a minimum of 20 years in prison.

Both Uniswap and Tornado Cash are smart contract protocols built on blockchain. Why are they treated so differently in terms of regulation? This article will delve into the two DeFi cases and analyze the underlying logic behind this differential treatment.

TL;DR

The technology itself is not guilty; it is the individuals who use the technology that can be guilty.

The ruling in the Uniswap case is a positive development for DeFi, as DEXs are not responsible for user losses caused by third-party token issuances. This impact is actually bigger than the Ripple case.

Judge Katherine Polk Failla also presided over the SEC v. Coinbase case. Her response regarding whether crypto assets are securities was, "This is not a decision for the court but for Congress," and "ETH is a commodity." Can the same interpretation be applied to the SEC v. Coinbase case?

In the Tornado Cash case, while third-party involvement triggered regulatory intervention, the severity of the case stems from the founders knowingly enabling the protocol to facilitate illicit activities that infringe upon national security interests.

Uniswap, as a U.S.-based entity, actively cooperates with regulators and its token's sole governance function serves as a good example for other DeFi projects in dealing with regulation.

1. Investors Sue Uniswap for Investing in Fraudulent Tokens

(https://uniswap.org/)

In April 2022, a group of investors collectively sued the developer and investors of Uniswap—Uniswap Labs, its founder Hayden Adams, and its investment firms (Paradigm, Andreesen Horowitz, and Union Square Ventures), accusing the defendants of not registering under the U.S. Federal Securities Law and causing damages to investors by listing "scam tokens." They are seeking compensation for the damages.

The presiding judge, Katherine Polk Failla, stated that the true defendants in this case should be the issuers of the "scam tokens," not the developers and investors of the Uniswap protocol. Due to the decentralized nature of the protocol, the identity of the issuers of the scam tokens is unknown to the plaintiffs (and also to the defendants). The plaintiffs can only sue the defendants in the hope that the court can transfer their claims to the defendants. The reason for the lawsuit is that the defendants provided convenience to the issuers of the scam tokens by offering an issuance and trading platform in exchange for transaction fees.

In addition, the plaintiffs played the role of SEC Chairman Gary Gensler, arguing that (1) the tokens sold on Uniswap are unregistered securities; (2) and as a decentralized exchange for trading security tokens, Uniswap should be registered with regulatory agencies as a securities exchange or securities broker. The court rejected extending securities laws to the actions alleged by the plaintiffs and concluded that the investors' concerns "are best addressed to Congress, not this Court," due to the lack of relevant regulations.

Overall, the judge concluded that the current cryptocurrency regulatory framework does not provide a basis for the plaintiffs' claims, and according to existing U.S. securities law, the developers and investors of Uniswap should not be held liable for any harm caused by third-party use of the protocol, thus dismissing the plaintiffs' lawsuit.

2. Disputed Focus of the Uniswap Case

Judge Katherine Polk Failla, who presided over this case, also presided over SEC v. Coinbase and has extensive experience in handling cryptocurrency cases. After reading the 51-page ruling, it is clear that the judge has a deep understanding of the cryptocurrency industry.

The focal points of this case are: (1) whether Uniswap should be held responsible for third-party use of the protocol, and (2) who should be held responsible for the consequences of using the protocol.

2.1 The underlying protocol of Uniswap should be distinguished from the issuer's token protocol, and the issuer implementing harmful actions should be held responsible

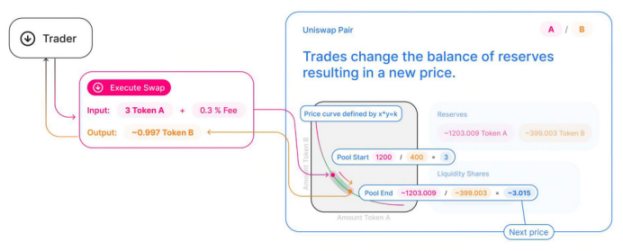

Uniswap Labs previously stated: "Uniswap V3's decentralized liquidity pool model is entirely composed of underlying smart contracts and automatically executed. This model, due to its openness, permissionlessness, and inclusiveness, can generate exponential growth of the ecosystem. The underlying protocol not only eliminates so-called intermediaries in trading but also allows users to interact with the protocol simply and effectively through various methods (such as entering through dApps developed by Uniswap Labs)."

The issuers themselves create and establish liquidity pool trading pairs (e.g., their own ERC-20 tokens/ETH) for investors to trade based on the aforementioned underlying Uniswap protocol and the unique AMM mechanism of DEX, without any form of behavioral verification or background checks.

(https://www.docdroid.net/APrJolt/risley-v-uniswap-PDF)

The decentralized nature of Uniswap means that the protocol cannot control which tokens are issued on the platform or who interacts with them. The judge stated: "These underlying basic smart contracts are different from the token contracts drafted by the issuers that are unique to each liquidity pool. The protocol related to the plaintiff's claim is not the underlying protocol provided by the defendant, but rather the liquidity pool trading pair protocol or token protocol drafted by the issuers themselves."

To explain further, the judge made several analogies: "It is like holding the developer of an autonomous vehicle responsible for a third party using the vehicle to cause a traffic accident or rob a bank, regardless of whether or not the developer was at fault." The judge also compared payment apps Venmo and Zelle, stating, "The plaintiff's lawsuit is akin to trying to hold these payment platforms responsible instead of the drug dealers for the funds transfer in drug transactions."

In these cases, the responsibility of individuals who engage in harmful behavior should be pursued, rather than blaming the software developers.

2.2 The First Judge in the Decentralized Smart Contract Context

The judge acknowledges the lack of judicial precedents related to DeFi protocols and their smart contracts. There have been no court rulings specifically addressing decentralized protocols and the means of holding defendants legally responsible under securities laws.

The judge believes that in this particular case, the smart contracts of the Uniswap protocol were indeed able to operate legally, just as they facilitate the trading of cryptographic commodities such as ETH and Bitcoin.

In this statement, the judge explicitly mentions the commodity nature of ETH, albeit briefly.

2.3 Investor Protection under Securities Laws

Section 12(a)(1) of the securities laws grants investors the right to sue sellers for damages resulting from violations of Section 5 of the securities laws (registration and exemptions of securities). Given the regulatory challenge of determining whether crypto assets are securities, the judge expressed, "This is not for the court to decide; it's for Congress to decide." The court declined to extend the securities laws to cover the defendant's alleged actions, noting the lack of regulatory foundation, and concluded that "investor concerns are best addressed to Congress, not this court."

2.4 Summary

While SEC Chairman Gary Gensler has avoided categorizing ETH as a security, Judge Katherine Polk Failla directly referred to it as a commodity (Crypto Commodities) in this case and refused to expand the application of securities laws to encompass the plaintiff's allegations against Uniswap. Considering that Judge Katherine Polk Failla also presided over the SEC v. Coinbase case, can her responses regarding the classification of crypto assets as securities, "This is not for the court to decide; it's for Congress to decide" and "ETH is a cryptographic commodity," be similarly interpreted in the SEC v. Coinbase case?

Anyway, although there are currently laws being formulated around DeFi and regulatory agencies may one day solve this gray area. However, the Uniswap case does provide a sample for the encrypted DeFi world to deal with regulation, that decentralized exchange DEX is not responsible for the losses suffered by users due to tokens issued by third parties. This is actually more significant than the impact brought by the Ripple case, which is good for DeFi.

(https://twitter.com/dyorexchange/status/1697332141938389281)

3. Tornado Cash in the depths of hell and its founder

Tornado Cash, a DeFi protocol also deployed on the blockchain that provides coin mixing services, doesn't seem to be doing well. On August 23, 2023, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) brought criminal charges against Tornado Cash founders Roman Storm and Roman Semenov, accusing them of conspiring to launder money, violating sanctions, and operating an unlicensed money remittance business during the operation of Tornado Cash.

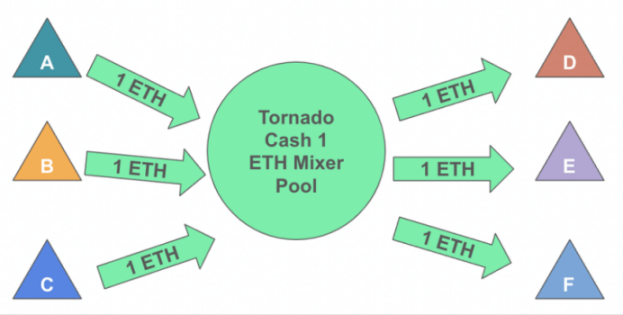

Tornado Cash is a well-known coin mixing application on Ethereum, aimed at providing privacy protection for user transactions. It achieves privacy and anonymous transactions by obfuscating the source, destination, and counterparty of cryptocurrency transactions. On August 8, 2022, Tornado Cash was sanctioned by the U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), and some on-chain addresses related to Tornado Cash were included in the SDN list, meaning that any entity or individual that interacts with the on-chain addresses in the SDN list is illegal.

In the press release, OFAC states that since 2019, the amount of funds used for money laundering crimes through Tornado Cash has exceeded $7 billion. Tornado Cash provides substantial assistance, sponsorship, or financial and technological support to illegal online activities both inside and outside the United States. These actions may pose significant threats to U.S. national security, foreign policy, economic health, and financial stability, and as a result, they have been sanctioned by OFAC.

(https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Example-of-the-Tornado-Cash-1-ETH-pool-addresses-A-through-F-deposit-to-and-withdraw_fig1_357925591)

3.1 Criminal Charges against Tornado Cash and its Founders

In the DOJ's press release on August 23, it stated that the defendants and their conspirators created the core functionality of the Tornado Cash service, paid for the operation of critical infrastructure to promote the service, and earned millions of dollars in return. The defendants knowingly chose not to comply with legal requirements for Know Your Customer (KYC) and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) due diligence, despite being aware of the illegality of the transactions.

In April and May 2022, Tornado Cash service was used by the Lazarus Group (a sanctioned North Korean cybercrime organization) to launder hundreds of millions of dollars in hacker profits. It is alleged that the defendants knowingly facilitated these money laundering transactions and made changes to the service in order to publicly claim compliance with regulatory requirements, but privately acknowledged that these changes were ineffective. Subsequently, the defendants continued to operate the service, facilitating hundreds of millions of dollars in illicit transactions and assisting the Lazarus Group in transferring criminal proceeds from OFAC-designated blocked cryptocurrency wallets.

The defendant is charged with one count of conspiracy to commit money laundering and one count of conspiracy to violate the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, both of which carry a maximum sentence of 20 years in prison. They are also charged with conspiracy to operate an unlicensed money transmitting business, which carries a maximum sentence of five years in prison. The federal district court judge will decide how to sentence them after considering the US Sentencing Guidelines and other statutory factors.

3.2 Definition of Money Transmitting Business

It is important to note that the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), a subsidiary of the US Department of the Treasury, has not filed any civil lawsuit against Tornado Cash and its founders for operating an unlicensed money transmitting business. If Tornado Cash falls within the definition of a money transmitter, it would imply that the same definition applies to other similar DeFi projects. Once confirmed, these projects would need to register with FinCEN and go through KYC/AML/CFT processes, which would have a significant impact on the DeFi world.

In 2019, FinCEN released guidance (2019 FinCEN Virtual Currency Guidance) categorizing business models involving cryptocurrency activities and determining whether they fall under the definition of a money transmitter based on their nature of operations.

3.2.1 An Anonymizing Software Provider

Peter Van Valkenburgh from Coin Center stated that the only allegation in the indictment regarding the defendant's operation of an unlicensed money transmitting business is that they engaged in a business of transferring funds on behalf of the public without being registered with FinCEN. However, in reality, Tornado Cash serves as an anonymizing software provider, providing delivery, communication, or network access services for currency transmission services used by currency senders.

The 2019 guidance explicitly states that an anonymizing software provider does not fall under the definition of a money transmitter, whereas an anonymizing service provider does.

3.2.2 CVC Wallet Service Provider

Top law firm Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP has also released a report that analogizes the only business defined as a money transmitter in the 2019 guide – cryptocurrency wallet service provider (CVC Wallet) – to the rigid requirements of money transmitters. The report states that money transmitters must have total independent control over the value being transmitted and that this control is necessary and sufficient.

In this case, the complaint alleges how the defendant controls the Tornado Cash software/protocol, but it does not specify how the defendant controls the transfer of funds. The report analyzes the process of fund transfer in Tornado Cash and ultimately concludes that it does not have complete control over the transfer of funds like a cryptocurrency wallet service provider because the transfer of funds still requires user interaction through keys, and therefore should not fall under the definition of a "money transmitter."

3.2.3 DApps

Delphi Labs' general counsel @_gabrielShapir 0 disagrees with Cravath's viewpoint. He believes that Cravath overlooks another business model of cryptocurrency activities mentioned in the 2019 guide – Decentralized Applications (DApps).

(https://twitter.com/lex_node/status/1698024388572963047)

Here is FinCEN's perspective on DApps: "The owner/operator of a DApp may deploy it to perform various functions, but when the DApp engages in money transmission, the definition of 'money transmitter' will apply to the DApp, or to the DApp's owner/operator, or to both."

The complaint is based on the 2019 guide's understanding of DApps, defining unlicensed money transmission businesses as entities (individuals, corporations, non-incorporated organizations) that operate money transmission businesses through smart contracts/DApps, thereby subjecting them to FinCEN's regulations.

If FinCEN's guidelines in 2019 do indeed state as stated above, then we have to question why it has not taken any enforcement action against DeFi to clarify this interpretation since its publication. Considering that DeFi should all involve some form of fund transfer, theoretically it could apply to every DeFi application (since they all involve some form of fund transfer).

3.3 Summary

FinCEN's 2019 guidelines are ultimately just guidelines. They do not have any binding force or legal effect on the Department of Justice. However, given the current lack of a comprehensive regulatory framework for cryptocurrencies in the US, these guidelines are still the best document reflecting the regulatory attitude.

However, the actions of the DOJ leave important unanswered questions for the future of decentralized protocols, including whether individual actors should be held accountable for actions taken by third parties or resolutions resulting from loosely organized community voting. Roman Storm, a US defendant, will appear in court and face trial in the coming days. The court may have the opportunity to address these unresolved issues afterward.

Attorney General Merrick Garland stated, "The indictment sends a warning to those who think they can use cryptocurrency to conceal criminal activity." FBI Director Christopher Wray added, "The FBI will continue to dismantle the infrastructure that cybercriminals use to commit crimes and profit from them, and hold accountable anyone who assists these criminals." This shows the firm stance of regulators on AML/CTF.

(https://techcrunch.com/2023/08/23/two-founders-behind-russian-crypto-mixer-tornado-cash-charged-by-u-s-federal-courts/)

IV. Why the stark contrast between DeFi protocols

The commonalities between the Uniswap and Tornado Cash cases are: (1) they are both smart contracts deployed on the blockchain and capable of autonomous operation; (2) both involve regulatory intervention due to non-compliant/illegal use of the smart contracts by third parties; (3) the question arises as to who should be held responsible for the damages caused by non-compliant/illegal actions?

The difference lies in:

In the Uniswap case, the judge determined that (1) the underlying smart contracts on the blockchain, distinct from the token contracts deployed by the issuer, were legally operational without issues, (2) the token contracts deployed by the issuer caused harm to investors, and (3) therefore, the issuer's responsibility should be pursued.

In the Tornado Cash case, the complaint stated that, although regulatory intervention was also due to the illegal use by a third party, the difference is that the founder of Tornado Cash knowingly controlled the protocol and facilitated unlawful activities, which infringed upon national security interests. It is obvious who should bear the responsibility.

(https://www.coindesk.com/policy/2021/10/19/defi-is-like-nothing-regulators-have-seen-before-how-should-they-tackle-it/)

5. Conclusion

On April 6, 2023, the U.S. Department of the Treasury released the 2023 DeFi Illegal Financial Activities Assessment Report, which is the world's first assessment report based on DeFi. The report recommends strengthening the regulation of U.S. AML/CFT and enforcing (including DeFi services) crypto asset activity business from a regulatory perspective, thereby enhancing compliance with U.S. bank secrecy law obligations.

It can be seen that U.S. regulation follows this approach, regulating the inflow and outflow of crypto assets from the perspective of KYC/AML/CTF, controlling the source. For example, Tornado Cash provides money laundering convenience to unlawful individuals. From the perspective of investor protection, it regulates the compliance of specific project operations. For example, in the case of CFTC v. Ooki DAO, the regulator intervened in law enforcement due to Ooki DAO's violation of CFTC regulations. In the case of Tornado Cash, the regulator intervened in law enforcement due to its violation of FinCEN's money transmission regulations.

Although the U.S. regulatory framework for crypto is unclear, currently, Uniswap has established operating bodies and foundations in the U.S. and actively cooperates with regulatory agencies to implement risk control measures (blocking certain tokens). Its UNI token has always been for governance purposes only (not involved in disputes over security-type tokens). These actions provide a good example for other DeFi projects in dealing with regulation.

Technology itself is not guilty; guilty are the individuals using technology tools. Both the Uniswap and Tornado Cash cases have provided the same answer.