Compilation of the original text: The Way of DeFi

Compilation of the original text: The Way of DeFi

Domothy and I co-authored this article. PBS remains an active area of research, but this comprehensive article aims to summarize the research progress to date and where research is headed.

image description

first level title

1. MEV quick start

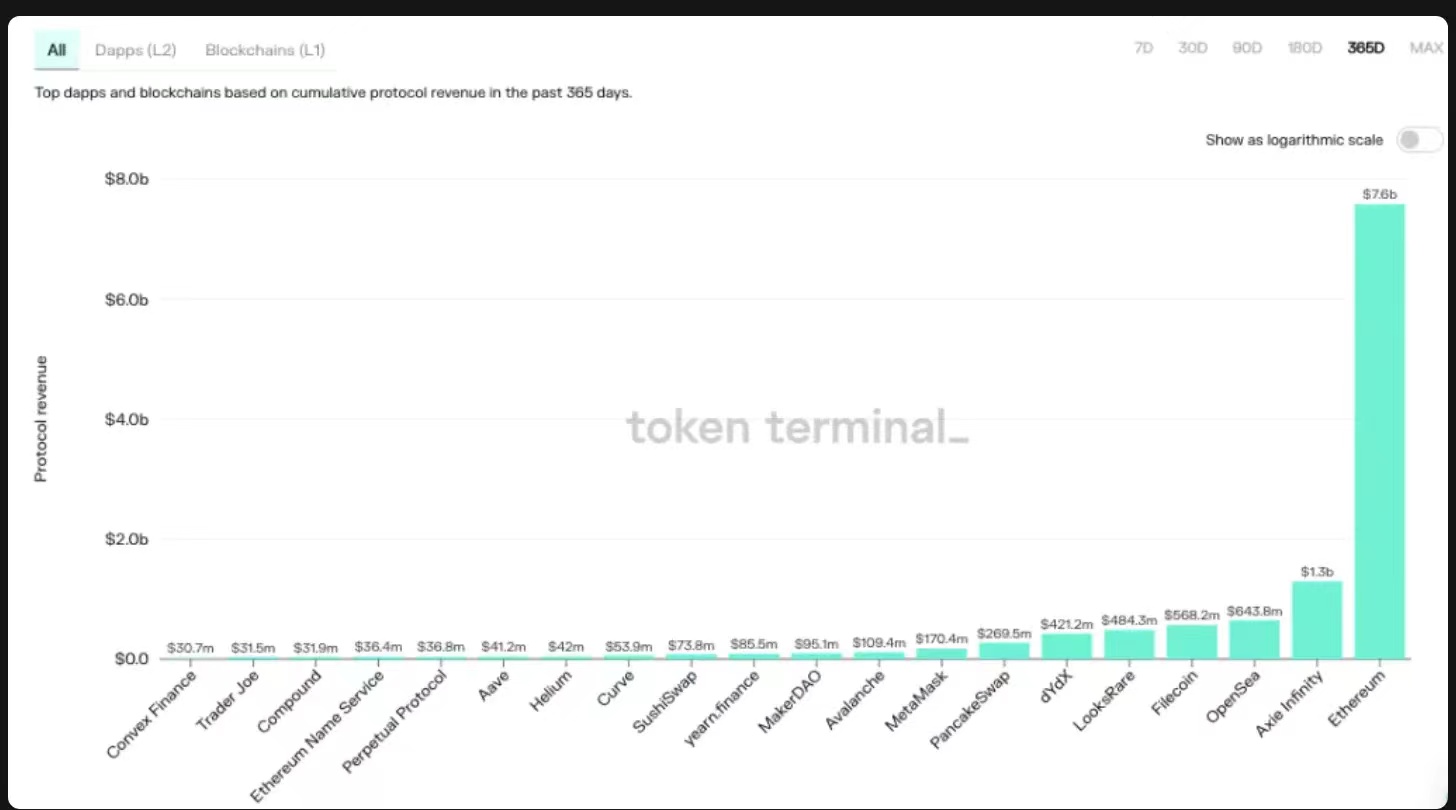

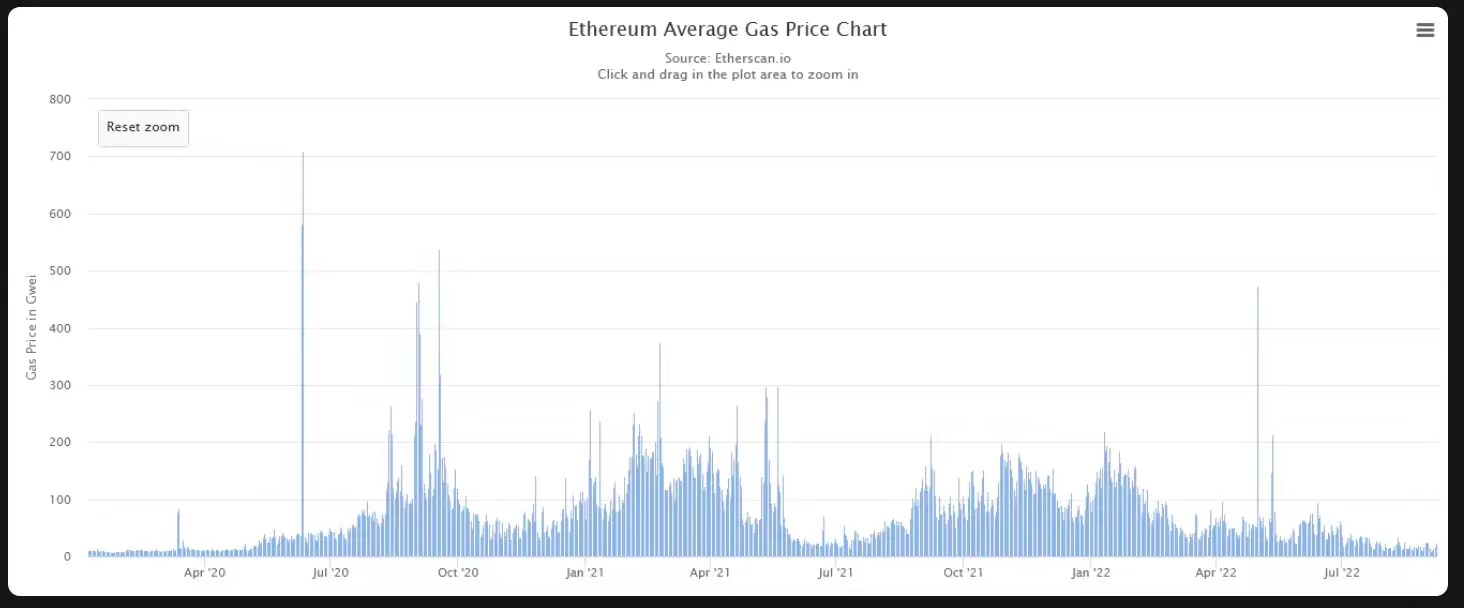

Technically, an Ethereum transaction is just a series of bytes. Therefore, the cost involved in creating and sending it is negligible. A good example is on-chain arbitrage. When the same asset is priced differently between exchanges, it creates opportunities for value extraction. Any money made from this transaction, minus the gas fee, is basically profit extracted from economic activity on the blockchain.

However, there is a problem here: due to the transparency of the blockchain, anyone with a node can identify and submit the same transaction. No matter how many people send their transactions, there will only be one winner: the person whose submitted transaction gets confirmed. As you might imagine, this greatly benefits whoever decides which transactions go into the next block, and in what order, they can simply take advantage of those transactions!

first level title

2. The development path of MEV

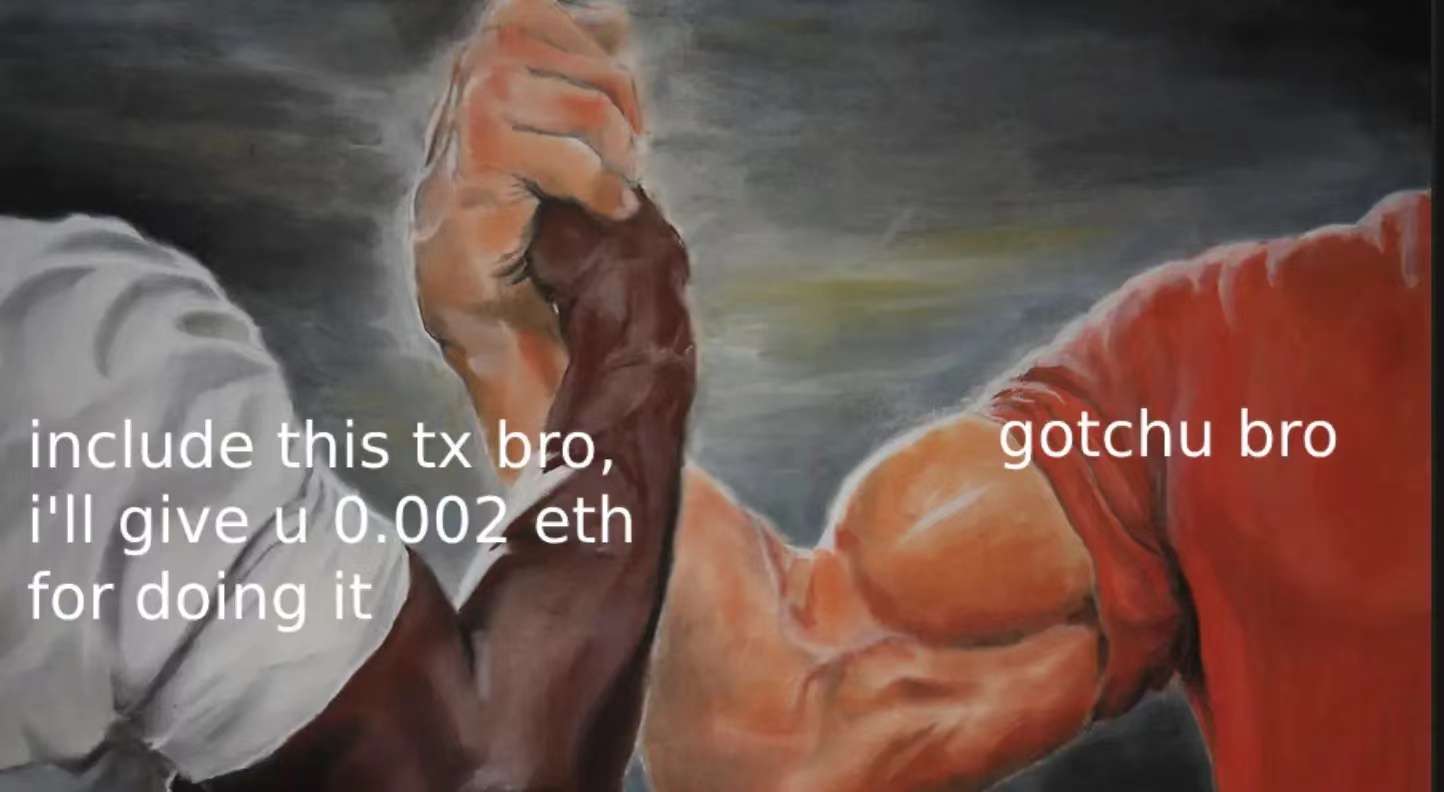

A few years ago, when Ethereum was still secured by proof-of-work (PoW), the concept of MEV was mostly theoretical. Instead, the transaction is simple: "Here's what I want to do, and here's the money I'm willing to give the miner to include it in the next block."

Miners will simply look at the list of pending transactions, sort by highest fee, and put as many transactions as possible into a block. The complexity of the transaction itself is irrelevant. This satisfies some notions of fairness: each miner will run the same code, follow the same rules, and earn the same amount of money (proportional to hashrate).

secondary title

Short term: gas wars

image description

secondary title

Mid-Term: Centralization of Consensus

As miners realize the power they have as block builders, a new centralizing force emerges. Block builders are guaranteed to include their MEV transactions regardless of the bid.

Note: After EIP-1559, block builders still need to pay a base fee.

secondary title

Long Term: Misaligned Incentives

This centralization leads to second-order consequences: in addition to ordering transactions in a block, block builders can choose to add their blocks as intended or roll back the blockchain by a few blocks, in order to Effectively "stealing" all MEV opportunities from recent deals. In some extreme cases, stealing the previous block's MEV may be the more profitable option, which could easily lead to an unstable blockchain constantly splitting into smaller forks, resulting in longer settlement times.

first level title

3. Potential solutions

secondary title

1. Mandatory ordering of blocks by fee

result:

(1) Back to the gas war;

secondary title

2. Enforce the random order of included transactions

Open-ended question: who decides what is random?

result:

(1) Back to the gas war;

(2) Increased the delay of transaction consensus;

secondary title

3. Encrypted storage pool

result:

(1) Reduction of toxic MEVs;

(2) Need to increase the verifier's honesty assumption;

(3) increase delay; (4) increase complexity;

(5) Increase censorship resistance;

(6) MEVs self-contained by validators are not affected

first level title

4. Block Construction Market

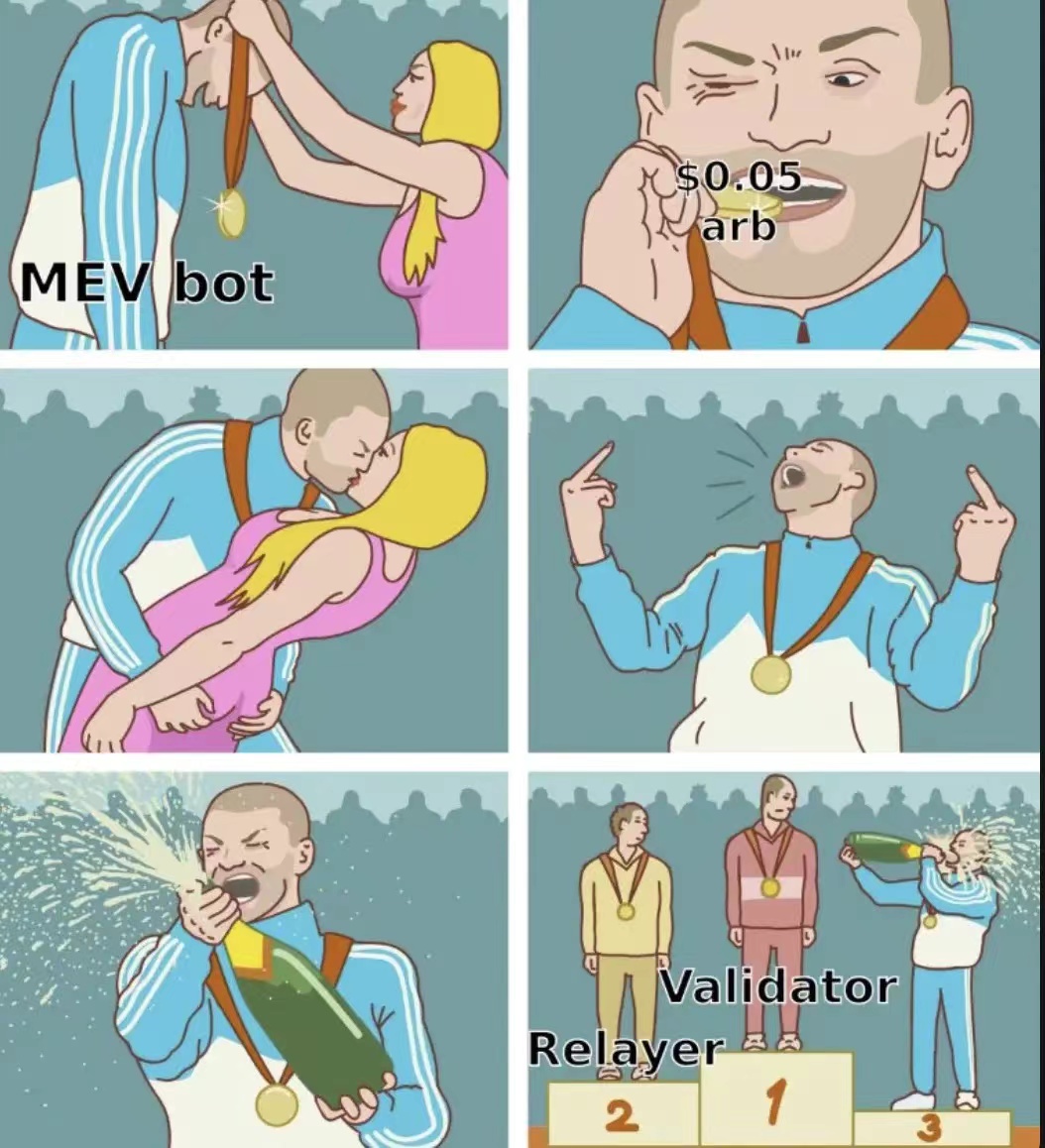

The solution is by separating the process of proposing a block from the process of building it, hence the name Proposer-Builder Separation. The idea of a "block proposer" already exists in Ethereum's PoS design. Every 12 seconds, a validator is elected as a block proposer. It doesn't matter how the blocks are constructed. The intended job of a validator is to propose it to the rest of the network, and it is the job of every other validator to verify it to make sure it doesn't break any rules.

The general idea of PBS is that block builders (builders) will compete and submit bids to any validator responsible for proposing a block. The only thing this validator needs to do is propose the block with the highest bid.

Using PBS, the highly confrontational MEV battlefield is carefully isolated to where block building occurs. Additionally, the auction system allows all validators to easily benefit from MEV opportunities discovered by block builders, regardless of size.

Giving up and turning the whole thing into a giant auction without actually trying to fix MEV itself doesn't seem like what we want to see. However, MEV is simply too lucrative to be considered some rare edge case. If we don't specify such an auction directly in the protocol, it will still exist in some form, except it will be out-of-band, opaque, and subject to the aforementioned centralizing forces. Left unchecked, it's easy to see what private block building auctions could look like, and all the damage they could do to the decentralization and trusted neutrality of the blockchain.

secondary title

Ideal market for block building

What should the ideal market look like?

1. Neutral

(1) Block proposers should not have incentives to favor certain block builders;

(2) Block builders should have no incentive to favor certain block proposers;

2. The smallest block proposer overhead

(1) Low hardware requirements allow more block proposers in the market;

3. Bundle Security

(1) Block proposers should not be able to intercept constructed blocks and replace their own transactions with MEV transactions;

4. Simplicity of consensus

secondary title

Existing market for block building

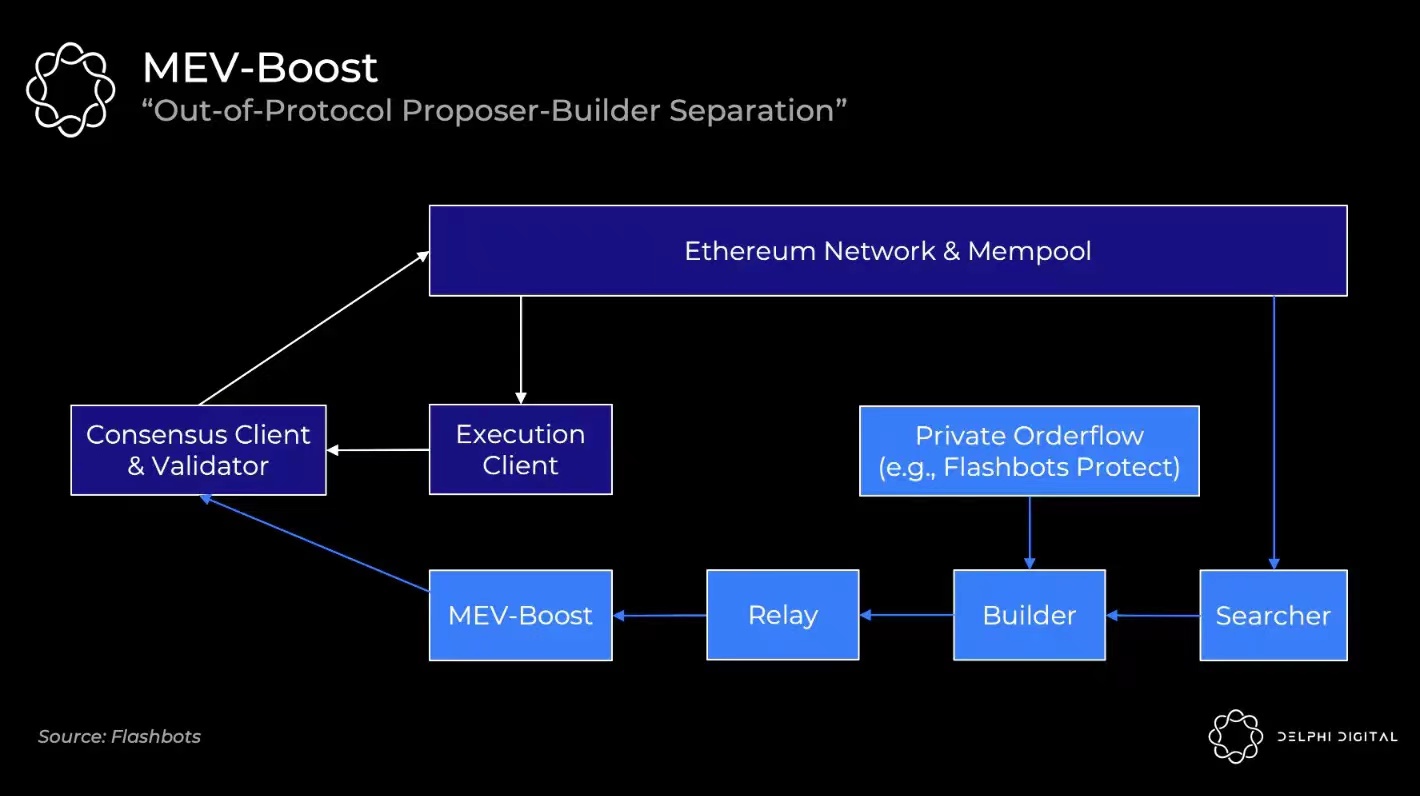

Implementing PBS directly in the protocol would be complex and take some time. At the same time, some off-protocol solutions have emerged to achieve the same goal, but they have some subtle tradeoffs. Although not formally written into the protocol, implementations outside the protocol allow for a higher degree of experimentation and provide an excellent testbed for the final implementation. Flashbots creates a block building marketplace with all-or-nothing bundles and conditional payments.

Their tools include:

1、MEV-Geth

(1) Not conducive to client diversity

(2) only work before the merge

2、MEV-Boost

(1) It has nothing to do with the client and solves the problems of previous implementations

(2) Validators cannot manipulate the block (they will only receive the block body after signing the block header)

But the off-agreement market still has some disadvantages:

(1) The relayer still needs trust

image description

first level title

5. Remaining questions

secondary title

1. Centralization of block builders

secondary title

2. Review questions

secondary title

3. High MEV difference

secondary title

4. Formal specification

first level title

6. Conclusion

A lot has happened in MEV and protocol research over the past few years, and the more we learn about it, the broader the topic becomes. While we still have unanswered questions, we are on the path to a decentralized, highly resilient, neutral global web. If you want to dig deeper, Domothy has put together a list of further reading here.

thanks for reading! We hope this helps. Follow @pseudotheos and @domothy on Twitter to get notified of future posts. This article is licensed under CC BY-SA. Thanks to Jon Charbonneau, Dmitriy Berenzon, and No Clue Capital for their feedback and comments.