Author: Alex Thorn; Michael Marcantonio; Gabe Parker

Compilation of the original text: Marina, W3.Hitchhker

Most people refer to buying NFT as "buying jpegs", that is, the avatars we see online and image files on trading markets such as OpenSea, but in fact the issuer of NFT still retains the ownership of these images.

We looked at the licensing of all the top NFT projects, and in almost all cases, issuers only offer usage licenses to NFT buyers, ranging from permitted usage to highly restricted commercial rights. In most cases, publishers are not honest at this point, often through omissions from their marketing content, which perpetuates the general "you own the artwork" misconception.

introduce

introduce

Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs) have opened the arena for building scarcity applications on the blockchain. These unique tokens have come to represent access rights, liquidity positions and works of art.

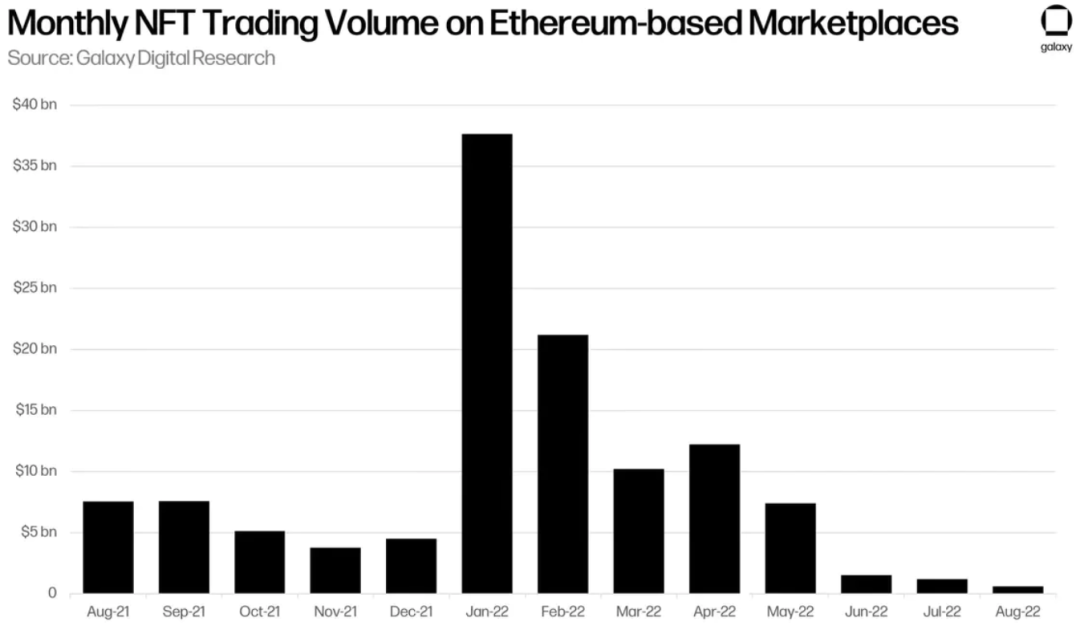

NFTs seem poised for a bright future with innovative applications both inside and outside the crypto-native ecosystem NFTs appear poised for a bright future with innovative applications both inside and outside the crypto-native ecosystem. Today, outside of certain DeFi use cases, NFTs representing works of art have seen the most adoption, with more than $118 billion worth of transactions on Ethereum in the past year alone.

Despite this “huge sum” and the way NFTs will revolutionize ownership, the reality leaves a lot to be desired. Contrary to the ethos of Web3, NFT holders today have zero ownership of the underlying artwork. Instead, NFT issuers and holders contain opaque, misleading, misleading and restrictive licensing agreements, and popular secondary markets such as OpenSea provide no such substantive disclosure to buyers.

Over the past few weeks, the cryptocurrency community has become more aware of intellectual property ownership and the fragile nature of NFTs, with two well-known issuers drastically changing the licensing of their NFT projects. Moonbirds, the eighth-ranked NFT collectible by implied market value, changed its license to Creative Commons (CC0) a few months after falsely claiming on its website that the holder "you own the intellectual property." And Yuga Labs, by far the largest NFT issuer, accounting for more than 63% of the market value of the top 100 NFT series, released a new license agreement for the two most original NFT series, CryptoPunks and Meebits. In this report, we explain the difference between terms of service, licensing, and intellectual property (copyright) ownership.

We observe major NFT collections by their implied network value, categorize the most common licensing agreements, and highlight iconic examples. We found discrepancies, in some cases, substantial and misleading, between issuer marketing materials and legal terms of service.

key points

key points

The vast majority of NFTs have zero intellectual property ownership of their underlying content (artwork, media, etc.).

Many publishers, including the largest Yuga Labs, appear to be misleading NFT buyers about the intellectual property rights of the content they sell.

Only one of the top 25 collections of NFTs by market capitalization even attempted to give intellectual property to its NFT buyers (World of Women).

Although Creative Commons licensing is seen as a solution to the restrictive licenses used by most projects, from a legal perspective, NFT holders cannot defend their ownership in court because NFTs completely transfer intellectual property to the public domain. Ownership of NFTs is obsolete to some extent.

first level title

What exactly are NFTs?

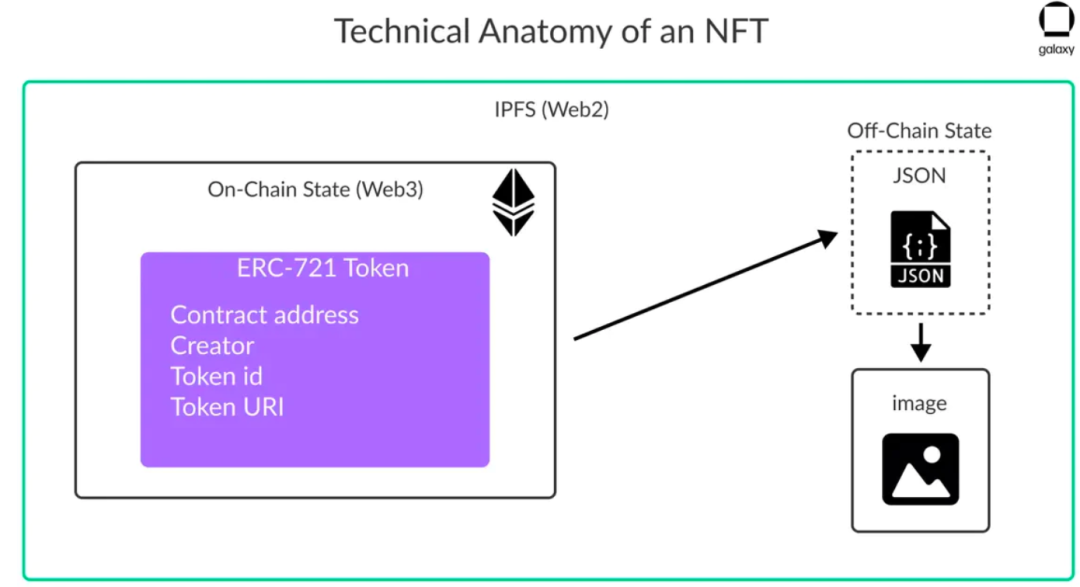

The distinction between NFTs and the digital content that NFTs point to is not widely appreciated or understood, even by the most experienced and sophisticated NFT holders. Most people think that when we buy an NFT, we're buying a digital image associated with that NFT -- an image stored on some blockchain, such as Ethereum or Solana. but it is not the truth.

Instead, what you are buying when you buy an NFT [1] is actually a combination of two different things:

A digital token, usually governed by Ethereum's ERC-721 standard, has a unique cryptographic address and contains certain metadata stored on the blockchain. However, that metadata isn't the image; it's data describing the image's location, usually off-chain, stored somewhere like Amazon Web Services or in the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS).

digital token

digital token

Fundamentally, like all digital assets, non-fungible tokens are just a few lines of code written on the blockchain. The difference between an NFT (such as the Bored Ape Yacht Club NFT) and a fungible token (such as LINK, UNI or WETH) is that the former is governed by the ERC-721 standard, while the latter is governed by the ERC-20 standard. The ERC-721 standard specifies certain criteria that a token must adhere to in order for it to be "non-fungible". Of these criteria, the two most important are tokenID (a unique identifier generated when a token is created) and contract address (essentially the address of the smart contract that generated the token).

first level title

license

The fact that an NFT "points" to an image does not, by itself, give the owner of that NFT any rights to that image, just like the NFT that minted the Mona Lisa gave the Mona Lisa's minter rights. Something more is needed, and this "something" is the owner of the image, known as the "copyright holder" — a legal agreement with the NFT holder that dictates what rights the NFT holder has over the image. If the NFT buyer has ownership, it does not come from his ownership of non-fungible tokens, but from the terms in the license issued by the NFT project party regarding the purchase and use of images by NFT holders.

Therefore, for most NFT projects, owning NFT does not mean that you own the corresponding digital content. It turns out that the content is owned and retained by the copyright owner (usually the NFT project party) associated with the digital content. In the United States, copyright is the only recognized legal form of ownership of digital content. Without copyright, buyers of digital content do not own the content, but rather "license" the content from the copyright holder on terms specified by the copyright holder. In this sense, the copyright holder (ie, the licensor) is the landlord of the digital content; the buyer of that content (ie, the licensee) is the tenant of the digital content. Admittedly, this digital landlord-tenant relationship isn't particularly problematic for most digital content; for example, no one thinks that buying a DVD or Blu-ray of the movie Young and Dangerous means you're buying Old and Dangerous. The exclusive copyright of the contents of "Aberdeen".

We are well aware that buying a movie on DVD or Blu-ray is buying a copy of some digital content owned by the studio that made the movie, not a unique collectible that grants exclusive rights to that content . But NFTs are different. NFT projects claim to sell unique digital collectibles that no one else can own. In fact, each image in the unique 10,000-piece collectible created by the NFT project represents a completely different work of art from all the others. Nobody thinks they're buying an NFT copy of a super-rare feature, they're buying the "rare feature" itself. In fact, the whole concept of "rarity characteristics" popularized by many NFT projects in the last year suggests that buying a specific NFT with "rarity characteristics" means buying a unique piece of art that no one else can own.

first level title

NFT ownership

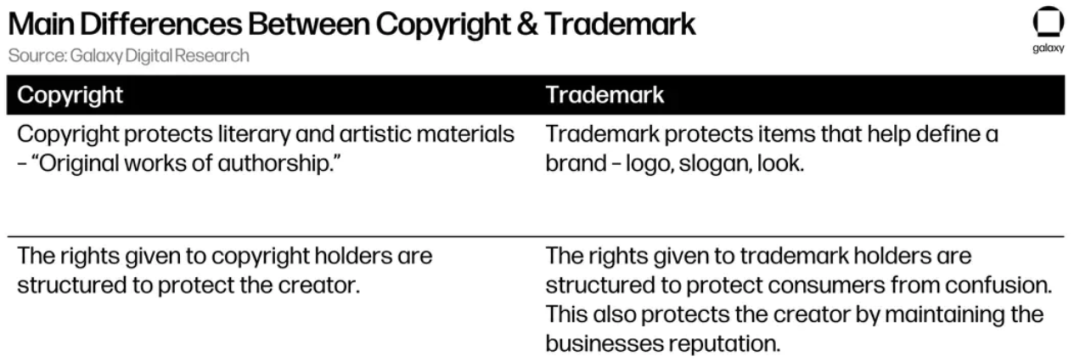

Owning an NFT means owning (1) a non-fungible token and (2) a license entitles the NFT holder to certain rights to the NFT image, which leads to questions about the nature of NFT ownership relative to copyright holders . Those interested in NFTs must understand the basics of copyright.

copyright

The copyright law of the United States protects "original works fixed in any tangible medium of expression". Once the author fixes the original and creative expression in a tangible form, the copyright automatically belongs to the author. This means that any artist who expresses a work in tangible form is automatically granted an enforceable copyright, without having to do anything.

Copyright law recognizes eight categories of protected works: (i) literary works; (ii) musical works; (iii) dramatic works; (iv) pantomime and choreographic works; (v) pictorial, graphic and sculptural works; other audiovisual works; (vii) sound recordings; (viii) architectural works. Accordingly, images associated with NFTs are subject to copyright protection under (v). This copyright protection, once acquired, gives the copyright holder a monopoly to (1) reproduce (2) distribute (3) publicly display (4) perform the work, and (5) create derivative works. Most importantly, copyright gives the copyright owner the right to do any of the above.

first sale principle

The second right listed above (right of distribution) gives the copyright owner the exclusive right to distribute copies of his copyrighted work, including in commerce, prohibiting others from participating in any such distribution. However, this exclusive distribution right of copyright holders to their copyrighted works is subject to an important limitation - the First Sale Doctrine ("FSD"). According to the FSD, a copyright owner's exclusive right to a copyright work ceases when it transfers ownership of a particular legal copy of its copyright work to a third-party purchaser. There is one exception to the FSD for digital works. Under the Copyright Act, the FSD does not apply to any person who has acquired the right to use a copy or phonogram from the copyright owner by renting, leasing, lending, or otherwise, without acquiring title to it.

Because FSD does not apply to rentals, an entire intellectual property architecture has been created over the past 30 years for licensing (rather than selling) digital works to allow copyright owners to retain their monopoly over the distribution of copyrighted material. So when you buy an e-book on the Kindle or a movie on the Apple TV, you're just buying a license to use that product under the specific conditions stated in the terms and conditions of sale. Since e-books and movies are not tangible products and exist in the digital realm, it is easier for the original owners of these goods to restrict use and withhold intellectual property rights, especially when the licensing platform is controlled by the publisher (Amazon, Apple).

Clearly, the lack of FSD implementation in the digital world makes the concept of true ownership extremely complicated, especially when it comes to NFTs. This is important: Most NFT buyers believe that when they buy an NFT, they own what the NFT points to. In this report, we looked at several top NFT collections and found that the vast majority of projects do not actually grant unique ownership of the content sold to NFT holders. There are several projects that are extremely misleading in giving NFT buyers intellectual property (or copyright) rights in the content they purchase. Some projects even explicitly state that NFT holders "own" the content, but then deny this fact in their terms of service.

Copyright and Trademark

first level title

How copyright is transferred in the real world

The right of copyright holders to distribute copyright works includes the rights of these holders to assign, transfer or sell their copyrights to third parties. In order to effect such a sale, assignment or transfer, the copyright holder must comply with certain statutory rules in order to certify the proper transfer of the copyright material.

Pursuant to Title 17, United States Code, Section 204(a), a valid assignment of copyright must be (A) in writing and (B) signed by or on behalf of the assigning party. While there is no statutory requirement to use a specific form to transfer legal ownership of copyright, most copyright transfers are made through so-called "intellectual property transfer agreements." For example, when Larva Labs sold its intellectual property in CryptoPunks and MeeBits to Yuga Labs, they executed the same type of agreement.

Types of NFT licenses

We looked at the top NFT collections by underlying market capitalization (base price * project size). According to our observations, NFT licensing agreements fall into four categories:

commercial rights

Freedom to monetize artwork - in any location or format, at any time, with no revenue cap.

limited commercial rights

Monetize artwork within a certain revenue range, or in a limited format or venue, for a specific time period. Typically this license is only available for low-price sales ($100,000 limit) of merchandise (ie T-shirts).

for personal use only

Artwork cannot be profited in any way and has limited display rights.

creative commons

Artwork can be used by the public. All of these licenses, regardless of level, come from the Web2 era. As we'll discuss in this article, the promise of Web3, that users will actually own digital property rather than rent it out, remains elusive.

commercial rights

An example of a license granting monetization rights to NFT holders is Azuki from Chiru Labs on the Ethereum network. The Azuki license grants unlimited monetization rights with no revenue cap and no restrictions on venue, format or duration. While Azuki is an example of a more permissive license than many other projects, Chiru Labs still grants zero-title ownership to NFT holders.

Chiru Labs may change and revoke the license at any time, for any or no reason. While Azuki owners can use and create derivative works, but not for another NFT project, Chiru Labs can also modify the base artwork at any time without reason, or create author works similar to your own adaptations, derivative works and modifications .

The ability for NFT holders to freely commercialize is powerful and distinguishes it from many other projects. Having said that, it is highly unlikely that any holder will engage in significant commercialization based solely on a unilateral agreement with the issuer which can be revoked at any time. Yuga Labs' projects Bored Apes Yacht Club, Mutant Ape Yacht Club, Bored Ape Kennel Club also fall into this category, but we will discuss these projects in more detail later in this report.

limited commercial rights

LSLTTT Holdings Ltd's Doodles NFT collection is an example where the license grants limited monetization rights. The Doodles license limits NFT holders to $100,000 in revenue from merch sales. In addition, the Doodles license prohibits modification of NFT artwork and expressly prohibits its use in any manner deemed illegal, fraudulent, defamatory, obscene, pornographic, profane, threatening, abusive, hateful, offensive Sexually obnoxious or unreasonable merchandise. While the terms are so broad that Doodles publishers can basically ban commercial use of any kind, they can update or modify the license at any time without actually needing any reason at all, and then make NFT holders comply.

The NFT License 2.0 (“NIFTY”) falls within the scope of the Limited Commercial Rights License. Another collection of NFTs that falls into this category is the iconic CryptoKitties.

for personal use only

The Veefriends NFT collection is an example of a highly restrictive, personal-use-only license. As of this writing, Veefriends is the 10th most valuable collectible by implied market capitalization, while VeeFriends Series 2 is the 14th. The holder of a "VFNFT" is granted a "limited license to access, use or store such VFNFT and its contents solely for personal, non-commercial purposes." The license goes on to expressly state that the VFNFT is "based on Limited edition digital creations of content that may be trademarked and/or copyrighted by VeeFriends".

Finally, the license states "Unless otherwise stated, your purchase of VFNFT does not grant you the right to publicly display, perform, distribute, sell, or otherwise reproduce VFNFT or its contents for any commercial purpose." Under this license, VFNFT holds People have no right to monetize the underlying artwork in any way, shape, or place, but holders can display the artwork for personal use.

Other examples of personal use licenses include TIMEPieces, adidas Originals, and NBA TopShots. The Veefriends NFT collection is an example of a highly restrictive, personal-use-only license. Holders of VFNFTs are granted a limited license to the VFNFT and its contents to access, use or store the VFNFT and its contents only for its own personal non-commercial purposes. And it is clearly stated that VFNFTs are limited edition digital creations based on content that may be trademarked/copyrighted, unless otherwise specified, the purchase of VFNFT does not confer any commercial purpose to publicly display, perform, distribute, sell or otherwise reproduce VFNFT or its content s right. According to this license, VFNFT holders do not have any rights to monetize artwork, but holders can display artwork. Other examples of personal use licenses include TIMEPieces, adidas Originals, and NBA TopShots.

creative commons

All of the licenses we have looked at so far have imposed a series of restrictions on the licensee's use and enjoyment of copyrighted material in favor of the copyright holder. In contrast, the CC0 license places no restrictions on the licensee's use and enjoyment of the copyrighted work. By adopting a CC0 license, the copyright holder effectively undertakes to waive all copyright and related rights in its copyrighted work to the fullest extent permitted by law.

Thus, the work is effectively "dedicated" to the public. Several prominent NFT projects have adopted the CC0 license, with mixed results. While the CC0 model undoubtedly has advantages over the existing licensing regimes described above, it also has significant drawbacks. In terms of benefits, holders of NFTs governed by CC0 have no restrictions on commercializing NFTs or using them in any way they see fit.

NFT holders managed by CC0 are on equal footing with creators of NFT projects when it comes to ownership of NFT art collections. While CC0-managed NFTs may benefit NFT holders by placing owners of NFT projects on an equal footing with NFT holders, they also place NFT holders on an equal footing with non-holders. Because once an artwork is in CC0, no one "owns" that artwork, meaning anyone can use it. This raises a question for the value props of CC0-managed NFTs: why would you pay big bucks for one when none of the NFT projects can preclude non-holders from exploiting the art associated with your NFT?

For this reason, many see the CC0 license as problematic for NFTs, as it enables anyone to use CC0-governed images without owning the NFT. CC0 NFT holders can commercialize their NFTs, but so can others. If CC0 NFT holders decide to commercialize the artwork, they will also not be able to legally protect such commercialization, they do not own the copyright and have no right to exclude others from using the same image. The "lil nouns" project is a perfect example, neither the holders of the Nouns DAO nor the Nouns NFT can enforce any kind of copyright infringement claim against the holders of Lil Nouns or their NFTs because Nouns are released under CC0.

CC functions similarly to CC0 when considering the dynamic relationship between copyright holders and buyers. Not all CCs are built in the same way though, with variations often coming from commercial and modification rights. Currently, CC0, CC-BY, CC-BY-SA, and CC-BY-ND are the only CCs that allow commercial use, and all CCs except CC-BY-ND allow the creation of derivative works.

A core issue related to NFT license agreements is the asymmetric control of licenses by copyright holders. If the copyright owner believes that the license agreement has been violated, they have the right to modify and revoke the license of the NFT holder at their own discretion. This ability to modify the license agreement at any time is a major flaw in the NFT architecture, and the rights of each NFT holder (especially, to the extent exploitable, its commercial use rights) can be legally limited or revoked completely. This would significantly inhibit the widespread use and adoption of NFT artwork.

Many of the license agreements we analyzed explicitly state that the NFT project (the licensor) has no responsibility or obligation to notify NFT holders of any amendments or amendments to the license, and it is the responsibility of each NFT holder to keep track of the project's license agreement on its website. latest terms.

in conclusion

in conclusion

In this report, we analyze the top NFT projects and group their related licenses into categories to assess what buyers actually own when purchasing an NFT.

We found that all but one license (namely CC0) retained all intellectual property rights in the artwork referred to by the NFT. In the case of a project attempting to create a collection of NFTs in which intellectual property is transferred from purchaser to purchaser, the design mechanism also raises questions about the validity of this transfer of ownership. Some issuers provided misleading statements that contradicted the terms of their relevant licenses. In some cases, these contradictions may be due to ignorance of intellectual property and digital rights.

Either the issuer deliberately misled the buyer, or misled the buyer by not explicitly correcting the market's misunderstanding of the buyer's ownership of its NFT and artwork. On the other hand, some projects have clearly disclosed the fact that NFT holders only own the NFT, but have no property rights. While there is no requirement for NFT issuers to explicitly grant full intellectual property rights to purchasers, the lack of intellectual property rights undermines the grand promises of NFT and Web3 promoters that this technology will revolutionize digital ownership.

If NFTs are to be widely adopted online, across Metaverse, and for commercial purposes, more durable frameworks for the assignment and transfer of intellectual property must be adopted. Even in the case of Creative Commons variants, issuers do not retain intellectual property rights to the underlying content of the NFT, NFT holders have no exclusive rights, and entrepreneurs cannot integrate NFTs into their businesses due to the lack of legal protection. Achieving a true future of digital ownership requires action:

NFT holders should fight for their intellectual property. Blockchain is very powerful in tracking ownership, not just licenses of artwork where the issuer retains ownership. It is unclear whether blockchain is needed if the use of NFT-related content is entirely dependent on the third-party issuer's permission. Beyond that, relying on the publisher's license puts the use of the content at risk. If the NFT issuer sells the underlying intellectual property to a third party, or is acquired outright, the new owner can unilaterally restrict, alter or remove the license entirely;

These protocols must be "solved" for Web3 to have a chance. There is also the question of how a limited commercial license (which can be revoked at will and does not transfer ownership of the digital content) reconciles with the ethos of Web3. The proposition that Web3 stands for is that the internet of the future will be owned by its users, not the big tech conglomerates. However, as this report shows, this commitment is not found in the terms and conditions of most NFT projects today, mainly because these terms do not confer ownership and transfer intellectual property rights to their holders; The limited Web2 license was extended in , failing to provide NFT holders with any say or control over the future of the art their NFTs are connected to. Since NFTs are still in their infancy, the NFT community must start developing a framework for properly granting IP rights to users before mass adoption. In the event that mass NFT adoption begins without addressing these pernicious IP ownership issues, NFTs will form Web2 products, but be marketed as Web3 products.

A decentralized metaverse requires intellectual property. If these problems are not solved now, the so-called decentralized virtual world is not fundamentally different from the virtual world being built by Web2 giants such as Meta (Facebook). In this case, the decentralized Metaverse will be decentralized in name only, utilizing only public blockchains and tokens to enable an efficient off-chain secondary market, but not passing on actual property rights.