Author: Packy McCormick & Tina He

Original editor: Nanfeng

Sometimes a token functions like equity in a company, and owning a token is akin to holding a stake in the project's potential earnings. Other times, the token functions like a "token of gratitude," symbolizing the purest kindness between close friends. Its broad role is not a bug, but a feature that represents value in the most abstract sense, with meaning given to it by the design of the system. In other words, Token does not necessarily have any intrinsic value, but relative value. It is an encapsulation of a unit of value universally recognized and enforced by a particular system.

Tokens are hardly a new concept. Shells and beads were the earliest tokens used as a medium of exchange. Others we are familiar with today—such as casino chips, credit card points, stock certificates, concert tickets, and club memberships—are tokens in various forms because they represent a universally recognized unit of value issued by the Token system enforcement. Jurisdictions can step in to protect token holders when their respective systems fail to enforce and recognize the value of these tokens.

Think about the token you’ve interacted with recently: what does it allow you to do that you wouldn’t be able to do without holding it? Why do you hold it and want to hold more? What happens if you give up or transfer ownership of Token? For many, the answer to these questions is "get more tokens". For others, holding Tokens gives them the right to participate in projects and communities that they care deeply about. The former involves the economics of holding Tokens, and the latter involves access rights.

Token design is poor when the accumulation of value in the system is inconsistent with the accumulation of value in the token. Gabriel Shapiro aptly described Tokens such as UNI, COMP, and the recently launched APE as "value by association" (value by association), because he keenly identified the fragmentation problem in the value flow of these Token protocols-the main value remains were given to insiders, while the "semblance of power" was distributed to others.

One of the reasons there is so much confusion about token design, and value accrual in particular, is that tokens, and the DAOs and protocols that issue them, are so all-encompassing. Sometimes issuers want their tokens to behave like company stock; others issue "governance" rights to circumvent regulation, while insiders buy up tokens in large numbers and want to exit before prices plummet; Hope to establish and unify the digital nation. Often, even the issuers don't know what they want to do with the token, but they know that tokens are a great way to capture value.

While token design is not the only important aspect of creating a new protocol or digital economy — providing value to users should always be a priority, otherwise token prices will inevitably collapse — it is a critical one. Just like a bad cap table can kill a startup, or bad monetary policy can derail a country's economy, bad token design can kill a protocol before it even gets off the ground. The cryptocurrency graveyard is full of examples of excellent projects whose token design from day one doomed their eventual demise—maybe token economics encouraged too much growth too fast—we’ll cover that in this article some of them. There are also some projects whose token design allows them to do things that non-Web3 companies cannot do by properly aligning incentives in the system and connecting the system to the larger ecosystem. We will also talk about these.

Why is this important? Everything is falling apart.Terra's CrashTo a large extent it is due to its Token design. Projects attracting millions or even billions of dollars in investment and promising ridiculous APY (annual yield) are learning the truth of the old adage "easy come, easy go". Here come the regulators. Tokens, which were worth a lot just a few weeks ago, have depreciated significantly.

All of these reasons, and more, are why understanding good token design is critical. Not only because good token design can help avoid catastrophic outcomes, but also because, assuming we're entering an ongoing crypto bear market, now is the perfect time to experiment with novel token designs without anticipating high prices and "only going up but not down" pressure.

Tokens are economic in nature; they have a price from inception and can be traded instantly on a liquid, global, 24/7 market. But the meaning of Token is much more than that. They are programmable primitives that allow DAOs and protocols to signal what is important in their ecosystems to reward good participation, transact with each other, build interconnected support networks, and support new digital organizations and nations form.

So what are you building? Are you building a club, a cooperative, a company or a country?

Protocols built can be all of the above, so we'll first describe how they compare to companies and countries, then develop a framework for token analysis and imagine what the world will look like after the dust settles. We hope this article is useful for builders, contributors, and investors.

definition

definition

Pause here and define three key terms that will help the entire article.

protocol:A logical system that coordinates interactions between providers and consumers of services based on rules written in code. For example, SMTP and Ethereum, which coordinate email, are both protocols. Ethereum captures value thanks to ETH.

Token:A unit of value generally recognized and enforced by the system that issues it. There are different kinds of tokens — including governance tokens, DeFi tokens, NFTs (non-fungible tokens), security tokens — that are designed to do different things. Tokens are code, and as such, they can be programmed to do almost anything their creators envision.

DAO:first level title

Compare Agreements to Companies

The simplest analogy for protocols is that they are like businesses, only digitally. DAOs are digital native businesses.

From a strategic point of view, it is convenient to think of protocols as corporations. There are countless books and frameworks on corporate strategy. "Competitive Strategy", "7 Powers", 5 Forces (Porter's five forces analysis model), "Good Strategy, Bad Strategy", etc., too numerous to mention. Most of the people who create and run protocols are from the corporate world (except those professors or students from academia). It is easy for us to transplant these ideas and experiences.

It's also convenient from a financial standpoint. There are many rules, textbooks, models, and entire industries based on company valuations. To understand a company, we need to understand how value is created, the sustainability and defensibility of value creation (unit economics and moats), and the governance and control dynamics (management team).

We arrive at the value of a company by looking at its net worth, which is the value of all assets minus all liabilities. A savvy investor looks at a company's assets and evaluates the quality of cash flow from each source to arrive at a fair value. Not all cash flows are created equal.

Excellent managers of traditional companies understand the perspective of investors, so they focus most of the company's resources on improving the core assets that drive corporate value, while ignoring or spending little energy on other aspects. Employees are allowed and encouraged to come up with ideas from the bottom up, but it's up to the CEO (and sometimes the board) to decide which ideas can turn value into core assets.

For a company like Meta (formerly Facebook), the core assets are user data and algorithms that deliver the right content for higher conversion rates. From trendy Instagram to highly utilitarian WhatsApp, Zuckerberg seems to be plotting trillions of things to collect more data, diversify its sources, improve data quality, reduce the risk of data irrelevance, and thus Improve the quality of core assets and their revenue-generating potential. Everything is provided to the core. This lack of focus on compounding effects is why companies that do a bunch of unrelated businesses (like conglomerates) tend to be undervalued.

Investors in Twitter have taken a similar approach to evaluating the protocol. Investors can conduct DCF (discounted cash flow) analysis to understand the accrued value of xSUSHI holders by predicting the growth of 0.05% fees generated by all transactions of the Sushiswap protocol (Note: Users can earn income by staking SUSHI tokens xSUSHI tokens. Specifically, the Sushiswap exchange will charge a fee of 0.3% for each transaction, of which 0.05% will be allocated to xSUSHI holders, and the remaining 0.25% will be allocated to liquidity providers). In addition to its core DEX (decentralized exchange), Sushiswap also provides a series of diversified financial products from lending to NFT markets. Investors may underestimate these non-core, ancillary cash flows as they are still early-stage and highly speculative and value the protocol primarily based on fees generated by its DEX. In this regard, protocols appear to be similar to corporations.

Both companies and protocols struggle to align human and financial capital to achieve a range of goals. The main objective of the company is to generate a return on capital invested. Many protocols certainly have a similar profit-making goal, but these tend to be more diverse — from maintaining a public digital infrastructure, to creating one of the most cost-effective lending platforms in the world.

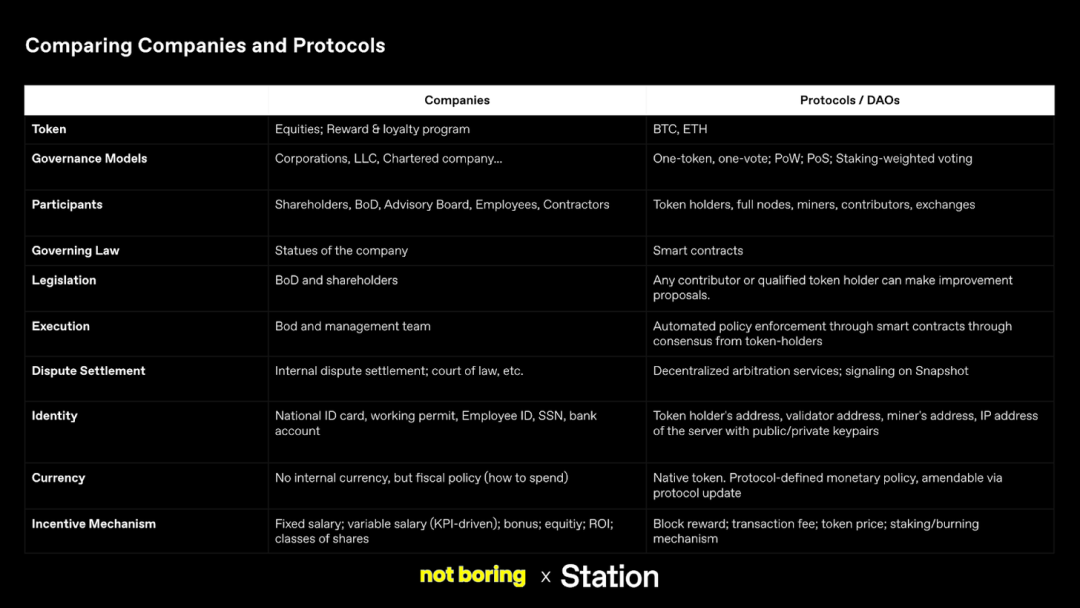

The similarities are evident when you look at all the functions of companies and protocols or DAOs line by line:

A quick glance at the table above reveals that DAOs and corporations do many of the same things. Both have various "Tokens", both need to establish governance models, both need to write governance laws, and so on. But a closer inspection reveals that there are major differences between the key entries.

Governance is the aspect that most clearly breaks the protocol analogy: corporate governance and protocol governance are very different. The former relies on centralized management, while the latter relies on the good judgment of Token holders.

In the beginning, the protocol can run like a business for a period of time, and the founders and core team need to make quick life-or-death decisions that startups need to make. But after they gradually decentralize, protocols need to completely hand over control to their communities. This presents a difficult trade-off: it is a challenge for protocols to maintain enterprise-style efficiency while including token holders in the decision-making process.

This is one of the few internal areas where companies and protocols differ.

From the outside, there are also big differences in where businesses and protocols derive their competitive advantage, and how they allocate value (i.e., how they maintain and distribute profits).

In an excellent article recently published for Harvard Business Review, "Why Build in Web3," Jad Esber and Scott Kominers explain that companies built in Web3 have different competitive advantages than those built in Web2.0. As highlighted above, in Web 2.0, one of the most powerful forces is data ownership, and the main moat is network effects.

Take Facebook as an example. Everything we do on Facebook is stored on Facebook's servers. All of this data allows Facebook to build features that keep you more engaged with its products and help advertisers better target you. Then, as your friends use Facebook more and more, your incentive to use and continue to use Facebook grows stronger. That's the story, you know.

And according to Esber and Kominers, Web3 is built differently:

Web3 is built on the premise that there is an alternative to monetizing user acquisition data — building an open platform that shares value directly with users will create more value for everyone, including the platform itself.

In Web3, users typically own ownership of any content they create (such as posts or videos) and digital objects they purchase, rather than the platform having full control over the underlying data. Additionally, these digital assets are often created according to interoperable standards on public blockchains rather than being hosted on a company's servers.

From a strategic perspective, data ownership and portability are perhaps the most important differences between Web2.0 and Web3. The implications of this subtle change - while far from being realized in the current instance of Web3 projects - are significant.

Take the "decentralized social graph" Lens Protocol as an example. Lens lets creators own their creations and bring them anywhere on the Web3. The agreement also creates a shared database of content and relationships between people, known as a social graph, on which anyone can build. The great power of social networking sites like Facebook and Twitter comes from the data they have, the social graphs that only they have access to. Lens envisions an internet where this is reversed, where data and social graphs are public and anyone can build on top of them.

As Web3 developer Miguel Piedrafita tweeted:

Not only does this mean that a rich app ecosystem can thrive by leveraging ever-growing sources of content and social graphs, but it also means that the sources of power and the accumulation of value change entirely. Don't like the Twitter algorithm? No problem, tap into all the underlying data and build something different. Creating a new social product is inherently a dead end—it's nearly impossible to channel the network effects existing companies have built up over the years—but Lens Protocol aims to eliminate the cold-start problem for social app developers, which could spawn more social applications.

As Esber and Kominers write:

The dynamics of Web3 are not a zero-sum game, which means that the overall value creation opportunity of a platform can be greater. Building on an interoperable infrastructure layer allows platforms to easily tap into the wider content network, expanding the scale and type of value they can provide to users.

While the opportunity for value creation may be greater, there are still some open questions about value capture. As Packy McCormick writes in "Shopify and the Hard Thing About Easy Things," "The hard thing about easy things is this: If everyone can do one thing, there's little advantage in doing it. But you still have to do it, just to not be left behind.” If these Web3 protocols make it easier for developers to build applications, then there may be more people building applications, competing for profits.

New Web3 primitives may spell trouble for existing networks, but it's still unclear where value will accrue in this new world. Esber and Kominers note that shared infrastructure has driven "a greater emphasis on platform design as a competitive advantage" and that "user insight continues to differentiate consumer applications." This appears to be a less durable competitive advantage.

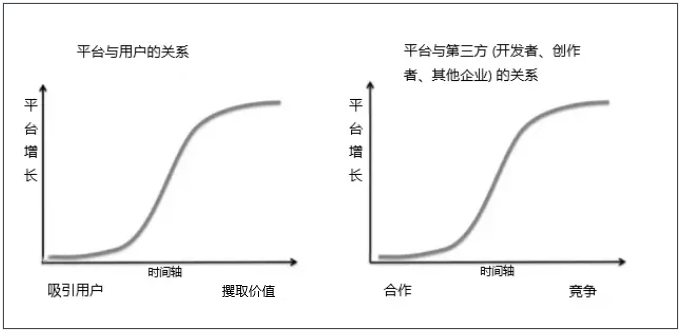

image description

Source: Chris Dixon

In Web3, when the content and social graph is open and anyone can build on top of it, it's hard for applications to get to the "Extract" (value-grabbing) phase, which happens to be where most of the profit happens . Users dissatisfied with an app can choose and move to another app, and dissatisfied developers can choose to fork the project or start their own projects on the same infrastructure, content, and social graph. This may be healthier for users, developers, and the overall ecosystem, but the prospects for app monetization are murky.

In this way, it appears that protocols can leverage “indirect” network effects to accumulate value. For example, as more developers build on the Lens protocol, they will attract more users who will share more content and social graphs with the protocol, making Lens an even more attractive option for the next developer. Obvious choice. Benefiting from the growth in overall usage of the platform, Lens Protocol can capture a lot of value in the form of fees, regardless of the stickiness of any specific application built on top of the platform.

But don't be so quick! In the classic "Protocols as Minimally Extractive Coordinators" article, Chris Burniske states, "As a coordinator of transactions, the protocol extracts as little value as possible." If a protocol's fee Too high, and if it shifts from "Attract" (attracting users) to "Extract" (grabbing value), developers will walk away with their users. Protocols are therefore incentivized to keep fees low enough to retain developers, while still capturing small enough profits that it doesn't make economic sense for a new protocol to try to compete. In other words, the agreement can still make money. As Burniske clarified (emphasis added):

I would specifically point out that grab-minimization does not mean that the cryptoasset that capitalizes the protocol captures the least amount of value; Coordinated assets can capture substantial value.

In theory, web3 will create more value, make it easier for applications to build open protocols and databases, and capture more value through Tokens, which are essentially related to the use of protocols and applications, and importantly, to building Shared value between investors and users, thus establishing a network effect driven by Token.

At this point, it's still early days, and the theory still needs to be tested on a large scale. But if the theory holds true, it's likely because of potentially the biggest difference between Web 2.0 companies and Web3 protocols: cryptographic assets, or tokens.

Tokens can provide superpowers to applications and protocols, provided they start with creating real user value. Given the scope of this article, we will focus on protocols.

Protocols need to do many of the same things as corporations, but they also face the additional challenge of coordinating a decentralized group of users/owners/contributors/voters. Fortunately, they have a trump card, the token, which gives them potential advantages in coordinating activities and capturing value, and also brings them builders and users. In that sense, they are not building companies, they are building economies.

first level title

Comparing Agreements to Countries

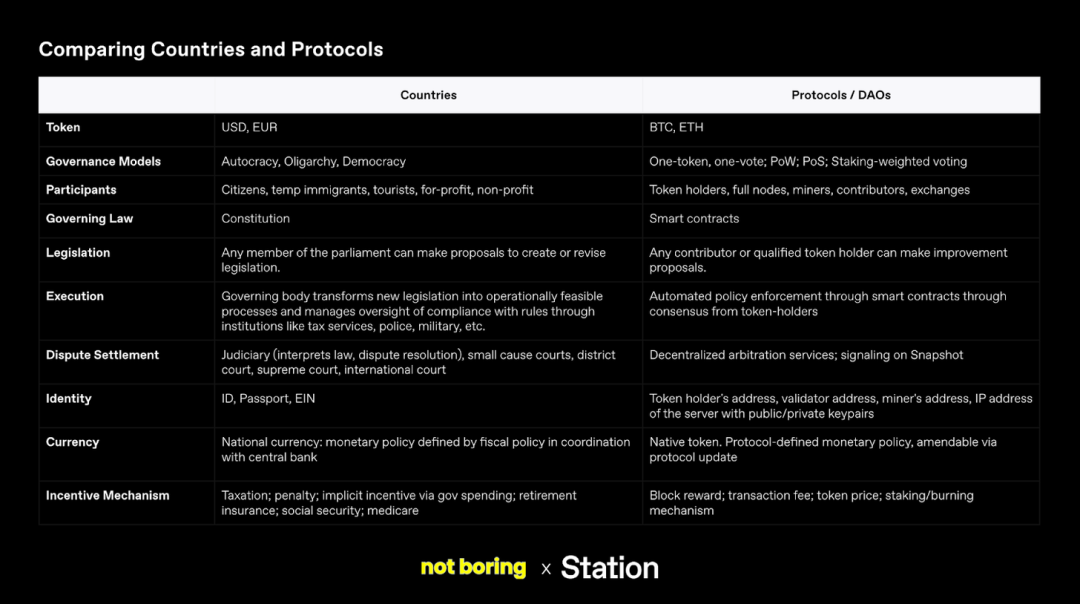

Less intuitively, the characteristics of decentralized protocols largely resemble those of nation-states:

The blockchain protocol establishes a country-like constitution and governing laws, while actors participating in the network are citizens of the network and are therefore bound by the laws and policies of the network.

Protocols need to do many things that national governments need to do: they need to establish governance, rules, balances of power, funding of public goods, identity standards, transaction policies, a currency (or two), and more.

The agreement defines the monetary policy, such as the Token issuance rate (inflation rate), and determines the conditions under which new Tokens will be minted. The nation's fiscal policy regulates taxation and government spending, while protocols typically collect transaction fees and reinvest DAO treasury into the development of the ecosystem.

As many would-be nation builders have discovered over thousands of years of human history, designing governance structures, rules, and policies to coordinate people and economies is no easy task.

Humans have been experimenting with economics and governance structures for millennia - with many mistakes and wars along the way. We still haven't got it right, but we've iterated on better models. Cryptocurrencies are trying to quickly run these same simulations over weeks, months, and years to determine the best way to govern and coordinate internet economic activity. Learning at a high rate means that big mistakes are bound to be made. The United States has fought through a War of Independence, a Civil War, and several foreign wars, some successfully and some unsuccessfully, to create, preserve, and spread its model of governance—democracy. Its economic system, capitalism, is a messy way to run an economy, but it ends up being far more effective than any attempt at massive central planning to date.

Crypto is an experiment in bringing a similar model to the Internet at the scale and speed of the Internet, and it is going through similar growing pains. We've all seen the last few weekswhat happened in terra。

The founders of the protocol often declared a national-scale thesis without adhering to the basic principles of economics-supply and demand. Yes, tokens can become valuable in the short term as containers for future prosperity, but the most important determinants of a token's continued value are:

the desirability of the underlying ecosystem;

Intrinsic utility of tokens in the ecosystem.

Without a clear understanding of how the ecosystem generates and captures value, it is nearly impossible to effectively fine-tune capital allocation strategies to create a long-term successful and resilient ecosystem.

A nation-state aims to increase productivity growth and competitive advantage in order to increase its long-term attractiveness and the strength of its residents, exports and currency. If analyzing protocol tokens is the art of microeconomics, then analyzing utility tokens for decentralized networks is the art of macroeconomics. The former requires supply and demand for products and applications, while the latter focuses on aggregate supply and demand dynamics within and across entire ecosystems.

In Why Nations Fail, economists Acemoglu and Robinson examine patterns in rich and developing countries. They observe that developed countries are rich because of their "inclusive economic systems" vs. extractive ones. Countries with what they call "inclusive" political governments—that is, those that extend political and property rights as widely as possible, while enforcing laws and providing public infrastructure—experience the greatest growth over long periods of time. By contrast, countries with "extractive" political systems (where power rests in the hands of a small elite) either failed to grow broadly or declined after brief economic expansions.

These lessons should be carefully considered when designing encrypted networks. From a development economics perspective, the need to decentralize political and economic power fits well with the design of blockchain networks themselves. The value of a blockchain network is largely determined by the quality of "natural resources" (block space and gas) and the demand for goods and services in the network. The United States also depends to a large extent on the quality of its resources: infrastructure, population, and natural resources. But good policy is also important, especially when it comes to coordinators.

Here, the similarities in structure and differences in execution between DAOs and states become apparent.

A friendly and transparent immigration policy that spurs innovation and provides education can be a country's most enduring strategic advantage. States can and do control who enters their borders (there are obviously exceptions), and can adjust quotas for immigrants from certain countries or with certain skills according to national priorities.

Right now in Web3, citizenship and identity, and immigration, are less clear. Currently, a democracy without a clear and unambiguous citizenship leaves protocols and applications open to attack. Tokens may provide a solution.

In the crytpo realm, citizenship is free to acquire and easy to buy. In most encrypted networks, anyone who owns a network token or runs a node can be considered a "citizen" of that network, even if the network never knows that person's identity. The lack of identity and accountability makes the protocol vulnerable to Sybil attacks and malicious governance takeovers. People can control multiple accounts at the same time, making the outcome work in their favor.

This is where NFTs come into play.

While traditionally NFTs have not been included in most conversations about token economics and token design, their inclusion expands the design space and opens up new solutions.

NFTs represent ownership and grant access to the holder, but the tradability of transferable NFTs makes such NFTs less attractive as an identity solution. And homogeneous tokens like ERC-20 are fungible and therefore a poor identity solution in their own right. It's like, you walk into a voting center and take out $1 as proof of identity to vote.

And the buzzword recently coined by Ethereum founder Vitalik Buterin "SoulBound Token” (SBT, Soul Binding Token) aims to solve this problem:

Non-transferable "soul-bound" tokens (SBT) represent commitments, credentials, and affiliations of "souls" (i.e., accounts) that can encode the real economy's web of trust to establish provenance and reputation.

These NFT-based digital passports, allowing users to carry their entire on-chain (and increasingly off-chain) history, contributions, work experience, and interests on Web3, will help enhance protocols and maximize differences between countries : That is, it is much easier to immigrate online than in the real world.

Packing and moving from the US to Canada can be a long, tedious, expensive and physical process. However, moving between different digital countries can be as simple as creating a new label.

With SBTs (soul-bound tokens), reputation systems like Station, and protocols like Lens Protocol growing in popularity, taking all your stuff (even your reputation) to a new DAO will much easier. Of course, you need to establish new relationships, but compared to moving from one country to another, switching between DAOs is almost effortless.

But unlike states, agreement citizenship need not be limited: a person may be an active citizen of ten or more different agreements. And it's not just citizens that the agreements themselves share with each other: like states, "trade" begins to build between the agreements.

As every digital economy grows, we start to see the rise of cooperation between protocols. Protocols are like countries, protocols come to understand their own competitive advantages, and everyone can be better off by establishing trade with their "neighbors". Metagovernance becomes a popular concept in early 2022:

Metagovernance means that protocol A holds the governance tokens of protocol B, and uses these tokens to vote on proposals in protocol B. It must be noted that there is no standard approach to meta-governance; a DAO will adopt a meta-governance mechanism and strategy that best suits the characteristics of its operations and goals.

Index Coop is currently leading an effort in meta-governance with its $INDEX token. The protocol creates an index of some of the highest quality blue chip tokens. One of the most popular of these indices is $DPI, which includes leading DeFi protocols such as Uniswap, Compound, Aave, and more. Therefore, buyers of $DPI, who are also holders of $INDEX, collectively own a considerable amount of $UNI tokens - enough to participate in the governance of Uniswap.

Organizations such as Wildfire DAO were created to create strategic alliances and collaborations between protocols to “bring together and align community members around the ecosystem, form new groups, and handle Token design, Governance and coordination issues.” These organizations are the UN, WTO, and IMF of the crypto world, protecting the well-being of the entire crypto ecosystem by coordinating incentives for key players. Becoming part of one of these groups symbolizes legitimacy, builds trust, but also comes with a set of constraints and terms imposed by the coalition, often imposed by more powerful players.

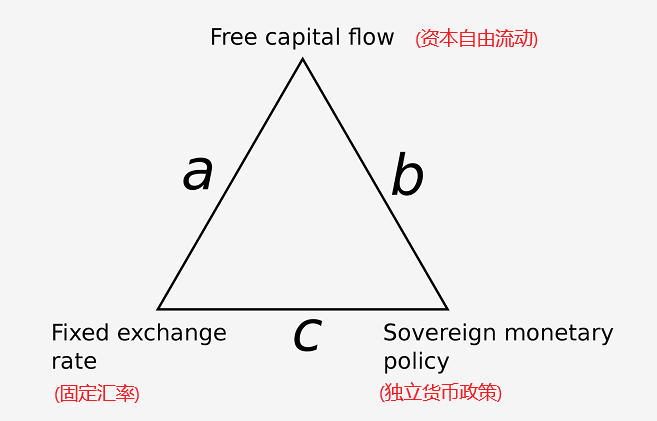

International economics may provide useful tools as we move from a closed economy to an interconnected one. An important concept supporting the field of international economics is the "Impossible Trinity" (Impossible Trinity, also translated as "Impossible Trinity"). In most countries, economic policymakers want to achieve the following three goals:

Open up the country's economy to international capital flows.

Use monetary policy as a tool to help stabilize the economy.

Keep currency exchange rates stable.

image description

https://www.moneyandbanking.com/commentary/2017/7/23/the-other-trilemma-governing-global-finance

Above: The Trilemma

Many protocols see this trilemma. If a protocol wants to use its tokens to invest in other protocols and receive external investment, while maintaining control over its monetary policy (token supply) to incentivize the development of the ecosystem, it must forego a fixed exchange rate with other tokens, which makes Protocol tokens become more volatile to hold or trade with as an asset.

Understanding these tradeoffs can help protocols position themselves strategically in the cross-protocol economy, allowing them to focus on strategic choices that align with their strategic strengths. Fortunately, the crypto community is very familiar with trade-offs and trilemmas, the most famous of which is blockchain’s “Scalability Trilemma.” Each protocol will be able to write into its code its design choices and the ways in which citizens can vote to make different choices.

first level title

A Token Design & Analysis Framework

This brings us to token design.

So where to start? The most important starting point is not monetary or fiscal policy—this is a mistake that many protocols have made; good token design, like good product design, starts with understanding what users want.

When consulting with new DAOs or crypto projects considering launching a new token, Station founder Tina He often starts with a simple question: What is the most important reason for people to join your ecosystem? This is the most valuable interaction (MVI, Most Valuable Interaction) in the network. The focus of Token design is to stimulate this MVI sustainable feedback loop.

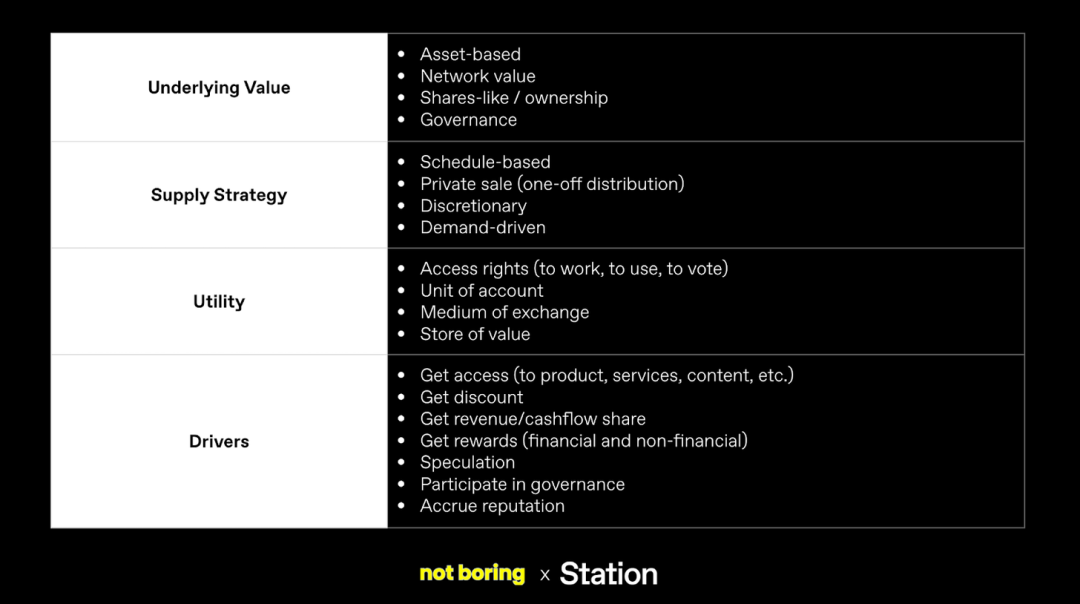

Based on MVI, token designers can use this simple framework to guide them:

Base value:What is the value of Token? Does it allow holders to vote, or own the network, or give them rights to specific assets? A protocol can have multiple Tokens, and these Tokens have different forms of basic value.

Supply strategy:How will the token supply grow or shrink? Is it determined by voters, or is it fixed from the beginning? If it is fixed, is the supply fixed, or is the formula that determines the supply fixed? There are some important trade-offs to consider, for example, the ability to correct mistakes in the token design against the confidence of knowing how the supply will evolve.

Effectiveness:What can token holders do? Does it give the holder access to jobs, events or markets? Can it be used as a medium of exchange in a protocol economy?

driving force:Why do people want to hold this token? In some cases, the answer may be as straightforward as "signaling status," as is the case with many NFT projects. Other tokens might offer users discounts on protocol products, or take a cut of their cash flow. There are also tokens that people want to hold just for speculation.

In a well-designed system, these things will be connected - for example, MVI should be tied into the driving force of the user, and supported by the utility of the token.

To illustrate this, we'll use an oversimplified example, at the cost of ignoring the complexity of many operations.

We assume a network's MVI (Most Valuable Interaction) is for Brazilian farms to contribute high-quality carbon credits to a network we call "AmazonDAO". If they get it right, there is an initial demand for these carbon credits: Google, Microsoft and other climate change companies want a premium supply of carbon credits. The challenge is the supply of carbon credits: out of the many carbon markets where these farms can contribute carbon credits, why should they choose and participate in AmazonDAO? Why is Token so important in it?

A successfully designed token should help achieve one goal: to make Brazilian farms want and continue to contribute high-quality carbon credits to the AmazonDAO network.

Market liquidity begets more liquidity. A premium supply of carbon credits could attract other market makers and buyers, which would increase demand, raise prices, and attract more supply. As with any new market, the challenge is to bootstrap (attract) initial liquidity. If we tell Brazilian farmers that if they become one of the early contributors to the network, they will not only receive a market-par dollar amount, but they will also become "owners" of a growing network run by small Comprising agribusiness owners, carbon credit buyers, carbon quality verifiers and agricultural researchers who come together not only to trade, but to share and create cutting edge knowledge and education to help agribusiness owners transform and improve sustainable agriculture practice. The quality of their approach and knowledge has attracted some of the top carbon credit buyers, sellers who want not only to acquire (buy) carbon credits, but also their brand, story and expertise to use in their own future strategic initiatives.

The network acts as a market maker, but instead of charging high intermediary fees, it pays the contributors and developers who created the initial network, with the bulk of the commission going directly to the network’s coffers: The Amazonian Fund. The fund is a transparent on-chain entity with a real subsidiary called AmazonianLLC. All token holders can decide who gets on the committee to interact with other legal entities as representatives. The most important decisions for the future of AmazonDAO are made by Token holders themselves—for example, whether they should invest more money in building local community centers and teaching more farmers how to produce qualified and sustainable coffee beans.

In summary: The main goal of the network is to attract and retain high-quality carbon credits, thereby attracting sustainable demand and growing the value of the network. Understanding these goals, we hope to design token models that clearly capture value and align incentives. We propose three tokens for AmazonDAO:

$AMA: A tradable, inflationary ERC-20 token named $AMA that represents ownership in the network;

$sAMA: A tradable ERC-20 token named $sAMA, representing staked $AMA tokens and governance power;

NFTs: A set of non-transferable NFTs (non-fungible tokens) that represent participants’ status in the network and provide NFT holders with access to different levels of products and services based on their past contributions .

The $AMA token serves as the network's unit of account and is used to track the relative ownership of each participant in the network. It also serves as a medium of exchange for compensating contributors and as a community currency on the AmazonDAO vertical, available only to NFT holders. The liquidity of $AMA provides speculative value to the token, attracting more outside interest and ways to reward contributors looking for short-term liquidity. The $AMA token is inflationary to match the growth aspirations of the network and appropriately incentivize newcomers while gradually diluting the power of early participants who cease to actively participate and contribute.

The $sAMA token represents the governance power, and the governance power will also be given a multiplier according to the length of the Token pledge. These staked tokens represent a vested interest in the long-term success of the network. All $sAMAs receive dividends (“yield”) paid out of the treasury based on their proportionate share of the total $sAMA. Early investors in AmazonDAO have staked their $AMA tokens and received $sAMA. They delegate most of their $sAMA to a few trusted leaders of good judgment in the network.

Last but not least, non-transferable NFTs known as AmazonDAO Passports are unique identifiers for each contributor to the network, including small agricultural business owners, carbon credit buyers, carbon quality verifiers, and agricultural Researchers. The metadata ("attributes") of this NFT evolves as members contribute more carbon credits, create more research reports, participate in more community events, and participate more in governance. Members can also use the NFT in other places, such as their on-chain certificates. For community managers or leaders, they can use these NFT data to design more advanced logic, such as giving transaction fee discounts based on reputation. They can also perform advanced analytics on Dune Analytics to understand the health and diversity of the network.

The four pillars of the above Token design framework are intertwined throughout the design: fundamental value, supply strategy, utility, and driving force. For example, the $AMA token is inflationary (supply policy) and can be used as a unit of account and medium of exchange (utility). Token designers should keep these pillars in mind, but first, focus on MVI (Most Valuable Interaction) and how the token can serve and enhance a good user experience.

The simplistic case study above is intended to provide a blueprint upon which more complex mechanisms can be built. For example, if we wanted to introduce a vertical lending protocol to fund new agricultural facilities from DAO treasuries, we could model risk based on the past history of borrowers in the network. If we want this DAO to participate in inter-protocol economic activities, we can figure out where it fits in the broader ecosystem, what its comparative advantages are over potential "trading" partners, and refine our token design to address "Triple Paradox".

The simplicity of this illustrative example is also intended to show that,first level title

What the world will look like when the dust settles

Token design is not a panacea.

A company's legal structure and corporate plans support but do not determine its success. “Democracy is the worst form of government—besides all others that have been tried.” The success of a company or country is far more important than economic and governance design. Agreements are no exception.

Having said that, we believe that token design provides builders with a richer and more expressive toolset than companies or countries have had to date. Anything in legal documents or monetary policy can be expressed in code running on the blockchain, which has the advantages of strong commitment, lower friction, automation and lower execution costs.

Of course, so far, being the kind of people we are, we've mostly used this new superpower to try and bend the laws of financial physics to get rich quick. The results of these attempts have been disastrous and unsuccessful. But there are also less sensational examples that hint at the potential of thoughtful token design. Let's look at two of these examples:

Braintrust is a user-owned talent network that uses token economics to charge lower fees while incentivizing clients, talents, and nodes running on the protocol to do many things that traditional talent networks need to pay for. Four months later, its total service volume has grown from $37 million at the end of January to $68 million today. One experience that Braintrust gave us is that the value of Token to network participants should be higher than that of pure financial holders.

StepN is a Solana-based Move-to-Earn app that rewards users for walking, jogging or running outside. According to a TechCrunch article over the weekend, the app has between 2 million and 3 million monthly active users. Even more impressive, the platform uses its token design to let people do something that is good for them: walk, run or jog. To continue its success, StepN will need to tweak its token design so that the app can survive without a flood of new users and them buying sneaker NFTs; MVI (Most Valuable Interaction), and design Token to encourage more core behaviors.

Still, these are just a few early examples, and we've been talking about a big game of comparing agreements to countries. We are still a long way from this. But we believe that the models that emerge from this bear market will be more creative, thoughtful and revolutionary than anything seen so far. Founders and token designers can focus on building rich economies (rather than applications), with active "domestic activity" and "international trade". A well-designed token can both accelerate the type of activity required and capture the shared value among token holders (citizens of the DAO). They can experiment with new governance models that reward people not only for ownership, but also for participation and contribution, which is not possible or practical in real world countries.

This is a useful way to think about designing token economies: imagine being able to create any economic and governance model that exists today, with the added functionality of programmable money, code-based law and enforcement, and composability. Of course there are trade-offs - decentralization can mean slower decision-making, bugs in the code can be exploited quickly, etc. But we believe we are only at the tip of the iceberg. The craziest ideas haven't come yet, but are coming soon.

A bear market is a time for tinkerers to tinker quietly. Without upward price pressure, builders can create more inclusive, mission-aligned communities, curated by the token, but not for the token. During the last bear market, 99.999% of the world had never heard of DAOs or NFTs; any token that wasn't Bitcoin (and possibly Ethereum) was labeled a shitcoin. This time, builders have a wider design space at their disposal.

We use a decade to look at innovation, and on this timescale, we have no doubt that the models created during the bear market will coordinate organizations, movements, and states that will outperform today’s largest DAOs and protocols in terms of market capitalization Orders of magnitude larger, sure, but more importantly engagement will be as well.

Token design is just a tool, but it can be a powerful one. Go build the world.

Thanks to Tina for your talent, Dan for your editing, and Conner Swenberg and Mind Apivessa for your inspiration on this article!